|

Queen of Green - Herbivorous Fishes; Part 1

Part I in a Three Part Treatise on Herbivorous Fishes, Tropical Reefs & the Aquarium Industry Herbivorous fishes are the primary grazers in reef ecosystems, and many are fantastic aquarium fishes as well. These fishes control marine algae growth, enabling new coral recruits to effectively compete for space, thus contributing to the overall health of the ecosystem.

Part I

~

Part II

~

Part III

|

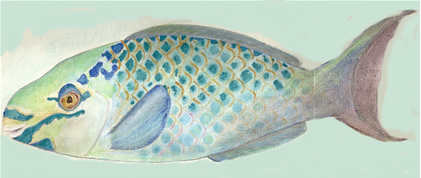

| Parrotfishes, such as this spotlight parrotfish (Sparisoma viride) photographed here by Peter Mumby, are important and well-known grazers on coral reefs. |

Herbivores occupy a critical ecological niche in the marine environment. While mollusks take the lead controlling marine algae in the intertidal zone and in our aquaria, herbivorous fishes fulfill this role on tropical reefs the world over. Controlling marine algae growth, which, once established, prevents new coral recruits from effectively competing for space, fulfills an essential, albeit little understood, ecological function. Some of these herbivorous fishes should be included in aquariaboth reef and FOWLR (fish only with live rock)and others should not. In addition to looking at the functional capabilities of several herbivorous fishes within their natural ecosystems, this series of articles will also consider the relationship between herbivorous species and the marine aquarium hobby.

Nobody Likes Excessive Algae

Most of us dont like excessive algae in our reef aquaria, and, by the same token, marine scientists dont like observing algae-dominated coral reefs. As tropical reefs continue to decline as a result of sea surface temperature warming, global climate change, terrestrial runoff, development of coastal tourism, and a variety of other factors, marine scientists are increasingly witnessing a phase-shift away from coral-dominated habitats towards algae-dominated habitats.

In the same way that reef aquarists often take a biological approach to algae control (e.g., introducing species that are known algae-grazers such as surgeonfishes), many marine scientists are taking a similar approach to degraded reef habitats by studying those herbivorous fishes best at controlling fast-growing macroalgae. Perhaps not surprisingly, much of their research has been focused on herbivorous fishes that are frequently seen in the aquarium trade, such as parrotfishes, surgeonfishes and rabbitfishes.

The Need to Maintain a Surplus of Herbivores

|

| Dr. Peter Mumby is a researcher studying parrotfishes on Caribbean reefs. |

The reefs of the tropical western Atlantic have suffered greatly over the past thirty years. A combination of diseases (such as the one that nearly wiped out all herbivorous urchins in the mid-1980s), coral bleaching events and the effects of development and overfishing have left many Caribbean reefs in a severely degraded state. According to some studies, herbivorous fishes are proving more important than ever before on these reefs.

The role of grazing is important because seaweed can prevent coral populations from recovering effectively, explains Dr. Peter Mumby, a professor of coral reef ecology at the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom. Mumbys research group is focused on the resilience of coral reefs, with an emphasis on studying the role of algae grazing parrotfishes in both the Western Atlantic and the Pacific. Seaweed prevents new corals from settling on the reef. Those coral recruits that do manage to settle suffer reduced growth rate, reduced fecundity and, in some cases, direct overgrowth (mortality) by algae. Thus, Mumby concludes, it is it important to maintain a surplus of herbivores in order to facilitate coral recovery after disturbance.

When grazing fishes are overfished, whether for food or for the marine aquarium industry, reefs suffer because algae outcompetes sessile invertebrates such as coral. Mumbys team, whose research was published in the journal Nature in a paper titled Thresholds and the resilience of Caribbean coral reefs in November 2007, was, according to Mumby, the first group to provide concrete evidence that herbivorous fishes are essential to the health of coral and, in turn, the tropical reefs built by coral. (Dr. Mumby has graciously offered to provide Blue Zoo News readers with a copy of the article by e-mailing him at P.J.Mumby@exeter.ac.uk and mentioning Blue Zoo. ed)

Coral reefs are unique ecosystems that have supported thousands of fish and other marine species for millions of years, says Mumby. We estimate that humans have already destroyed around 30% of the world's coral reefs, and climate change is now causing further damage to coral. These findings illustrate the need to maintain high levels of parrotfishes on reefs in order to give corals a fighting chance of recovering.

Parrotfishes Queen of the Herbivores?

|

| A spotlight parrotfish (Sparisoma viride) supermale photographed by a staff member of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. |

Given his research findings, one might assume that Mumby would not be a fan of the marine aquarium industry given that certain herbivorous fisheseven, at times, parrotfishesare perennial aquarium favorites. In reality, Mumby, while cautious about the industry, does see opportunities for the meeting of hobby and science in a concerted approach to conserving the natural ecosystems.

One of the weaknesses I've observed of the marine aquarium trade, Mumby says, is the lack of guidelines on sustainable levels of fish removal [by collectors]. His definition of sustainable, however, is different than what many aquarists think of when they hear the term. Mumby is less concerned with preventing fish species from becoming locally extinct and more concerned with sustainability from an ecosystem perspective. In order to [know what is sustainable], he says. We need to know how much grazing is needed in order to maintain a healthy reef and then ensure that sufficient grazing is carried out on the reef after fish are removed for food or the aquarium trade.

Ensuring that sufficient grazing is carried out on the reef after fish are removed, Mumby says, will require additional research, but, he points out, the same research could also add ecological value to the aquarium trade. For example, it would be useful to list the ecological importance of each species as one of its key attributes. We've started doing this for parrotfishes in the Pacific. The outcome would be a boost in education and appreciation of the role these fishes play.

|

| The bicolor parrotfish (Cetoscarus Bicolor ) is a fish commonly sold in the aquarium trade as a juvenile. |

To protect herbivorous fishes, Mumby advocates the responsible use of marine reserves or fisheries legislation. He does not advocate a blanket ban on any one particular species, although he does point out that all of the parrotfish species most commonly available in the hobby (e.g. Cetoscarus bicolor, Scarus taeniopterus, Scarus vetula, and Sparisoma aurofrenatum) are also important grazers on degraded reefs, especially the queen parrotfish (S. vetula). [The queen parrotfish] is probably the most important herbivore on many Caribbean reefs, says Mumby.

At present, the queen parrotfish is not considered at risk given current guidelines on sustainability, but that is based on species survivability versus ecosystem health. The species is not regulated by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), nor is it listed with the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) or the International Union for Conservation of Nature. For all intents and purposes, there is little to no regulation on this species for use in the marine aquarium industry. Nonetheless, Mumby thinks that the queen parrotfish, as well as the other parrotfishes seen in the trade, are good candidates for some type of management and regulation.

It's hard to recommend management strategies without estimates of the current extraction rates of these species for the aquarium trade, says Mumby. In general, it would be best to limit extraction of these species as much as possible and only take juveniles rather than adults.

Responsibility

In the interim, Mumby believes self-regulation of the marine aquarium industry is a good idea. I think self-regulation is always preferable [to legislation] and we, as scientists, have a responsibility for providing appropriate advice on collection practices. I'd like to see collaboration between the marine aquarium industry and scientists to generate practical advice that could then be implemented by the industry.

From the industry perspective, parrotfishes are not great aquarium fishes. As Bob Fenner, author of The Conscientious Marine Aquarist, says, [The parrotfish] would seem to have everything going for it as far as desirability to marine aquarists; many are spectacularly colorful, they have almost comical fusiform-torpedo body shapes, and they are numerous and easy to catch (at night) as they lay sleeping with or without their fish-made mucus cocoons. Their only downside, and it's a big one, is that [parrotfish] rarely live for anytime in captivity.

|

| The Queen Parrotfish (Scarus vetula ) may be the best grazer of all on Caribbean reefs and is frequently offered in the marine aquarium trade. |

The reason they often dont survive in the aquarium has to do with their diet, their adult size and their high levels of stress, which, more often than not, leads to disease. According to Mark Martin, director of marine ornamental research at Blue Zoo Aquatics, The only parrotfishes that can be recommended with any degree of integrity are the queen parrotfish (Scarus vetula), the spotlight parrotfish (Sparisoma viride) and the bicolor parrotfish (Cetoscarus bicolor). Even these three species are only recommended for public aquaria, scientists and expert aquarists who can provide a mature system of at least 150 gallons and are prepared to meet the fishs dietary needs.

What are the dietary needs of a parrotfish? Lets assume for a moment, says Martin, that these fishes do not stress out in the aquarium setting, and lets also assume that, after appropriate acclimation to ones tank, they swim around happily and appear to be the perfect aquarium resident. (By the way, Martin adds, neither of these are true statements.) The parrotfish would immediately start looking to graze for its preferred food, which is algae. In the wild, their specialized teeth are well adapted for scraping algae off of dead coral skeletons and sometimes living coral heads as well. They do this by taking a rather sizable chunk of the calcareous skeleton itself and processing whatever algae is on that skeleton inside its digestive system. The calcareous material is then excreted as waste creating brand new sand.

In a typical reef aquarium, we do not often keep dead coral skeletons as a matter of practice. What are left are living coral frags that the parrot fish will not differentiate from the dead stuff it is used to consuming. It will be more than happy to take chunks out of the living coral and process and utilize the zooxanthellae in the tissue of the coral as food energy. This would, of course, be a nightmare to most reef aquarists who keep expensive and difficult to find corals, but it would also prove disastrous to the parrotfish when the aquarist cannot keep up with the fishs needs.

If you really like the look of a parrotfish, Martin suggests, take a closer look at their cousinsthe wrasses, many of which do make excellent aquarium species and are much better suited for aquarium use.

A Sustainable Hobby Based on Science and Self-Regulation

In the final equation, aquarists should take note of the natural ecosystems from which the species they desire to keep are collected. As Mumbys research has shown, we need to learn a lot more about herbivorous fish species such as the queen parrotfish in light of degraded tropical reefs. As aquarists, we need to consider self-regulation based on science, even when some species have not been identified for protection by CITES or other regulating bodies. Building closer ties with the scientific community will provide the best opportunity for a sustainable hobby based on the conservation of sustainable populations of herbivorous fishes in the wild.

Article Resources

Video of Queen Parrotfish Feeding

Mumbys Research Group Webiste: www.ex.ac.uk/msel

Mumbys Coral Reef Video Web Resource: www.reefvid.org

Blue Zoo News Complete Interview with Peter Mumby

In Part II of this series on herbivorous fishes, we meet Dr. David Bellwood, whose research on herbivorous fishes on Australias Great Barrier Reef has somewhat complicated issues and shown us that we dont know nearly as much as we think we might about herbivorous fishes. According to Bellwood, we need to correct some common, albeit nave assumptions, about herbivorous fishes, because, as his research has shown, some of the most important grazers in terms of reversing the phase-shift back to coral-dominated habitats are awfully unusual suspects.

|