|

Daniel Pauly on Sustainable Fisheries & Fish as Wildlife

Towards Sustainable Fisheries and Seeing Marine Fish as Wildlife

Dr. Daniel Pauly is the Director of the Fisheries Centre (www.fisheries.ubc.ca) of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, where he is also a professor. Dr. Pauly received his doctorate from Kiel University in Germany and went on to perform field work in West Africa and Indonesia focused on developing new approaches for fisheries research and management. Dr. Pauly specifically chose to focus his work on data-sparse regions such as developing countries in the Tropics, and this eventually led him to Manila, Philippines and International Centre for Living Aquatic Resource Management (now WorldFish).

In 2002, Science Magazine called Daniel Pauly “arguably the world's most prolific and widely cited living fisheries scientist.” He has authored or co-authored over 500 scientific articles, book chapters and shorter contributions, and authored, or (co-) edited some 30 books and reports including In a Perfect Ocean: fisheries and ecosystem in the North Atlantic (Island Press, 2003) and Darwin's Fishes: an encyclopedia of ichthyology, ecology and evolution (Cambridge University Press, June 2004). His work has led to the creation of software like Ecopath (www.ecopath.org) and scientific databases like FishBase (www.fishbase.org), which are now used throughout the world.

Well respected by his colleagues, he is the recipient of the Oscar E. Sette Award from the Marine Fisheries Section, American Fisheries Society and the Murray Newman Award for Excellence in Marine Conservation Research from the Vancouver Aquarium. He was also awarded the 2005 International Cosmos Prize and the 2006 Volvo Environment Prize in 2006. Last year he was the recipient of the ECI Prize and Ted Danson Ocean Hero Award in 2007. He is a ‘Honorarprofessor’ of Kiel University and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada (Academy of Science). The New York Times has called Pauly an “iconoclast,” and he earned a place in the Scientific American 50 for his environmental work.

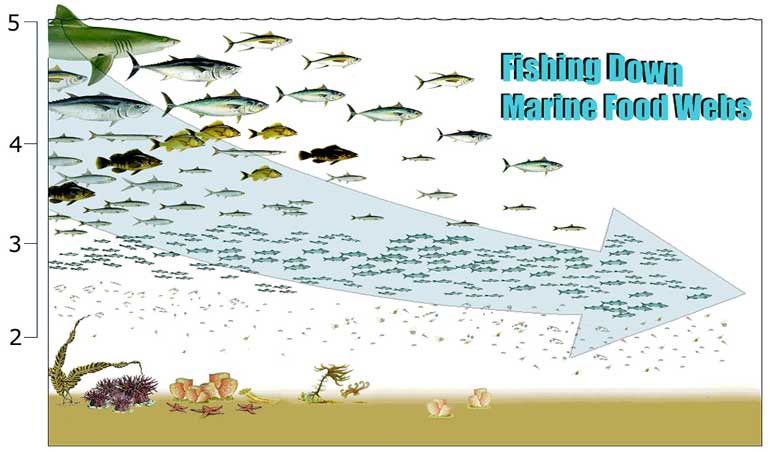

His current work concentrates on ecosystem-based fisheries management, and has led to concepts that are responsible for re-structuring much research in marine biology. He developed the overarching concept of “shifting baselines” in 1995 and published his seminal paper, “Fishing Down Marine Food Webs” in Science in 1998.

While not focused on the marine aquarium industry per se, Dr. Pauly’s experience and expertise provides valuable insight into the ecosystems and species upon which the aquarium industry is dependent upon. We are honored that he agreed to sit down with Blue Zoo News and discuss fisheries and some of his thoughts regarding herbivorous fishes and the marine aquarium industry.

BZA: Thank you, Dr. Pauly, for speaking with Blue Zoo News. For starters, have you ever had an interest in marine aquaria? If so, could you tell us a little about that interest?

DP: I definitely have a “brown thumb,” and all the aquaria that I ever started ended up as watery mass graves. The only exception was one large freshwater aquarium which I had when I was a student in Germany, and into which I put nothing but a scoop of pond mud. Over several weeks, then months, a surprising variety of plants and improbable small animals unfolded from the spores and eggs that had been in the mud, then passed on. It was eerie.

I often go to public aquaria. In fact, staring at the fish in the aquarium of the institute where I studied (which doubled as a public aquarium), watching them breathe and realizing that this is a hard thing for them to do, was the main inspiration for my doctoral thesis, which dealt with the relationship between respiration and growth in fish.

BZA: I have heard that you decided to pursue fisheries science because you “wanted to find an applied way to help people.” Do you feel you have helped people? If so, how?

DP: I wanted to acquire in Europe skills which would be useful in developing countries, where I planned to live, and I was able to that. As a result, many of the fisheries scientists now working in Asia, Latin America and Africa have been at training courses where I was one of the instructors.

Similarly, FishBase, which I initiated with Rainer Froese in the late 1980s, is now used by millions of people.

(Be sure to see Blue Zoo News’ interview with Rainer Froese. -ed)

BZA: You once likened the marine fisheries industry to “a terrible tenant who trashes their rental.” Do you include the marine aquarium industry in that statement? If so, what could be done differently?

DP: I don't know as much as I should about the aquarium fish industry, though what little I know suggest it is benign compared to the fishing industry. I do know of a few countries, though, where better regulations ought to be in place. In the Philippines, where I lived for many years, the aquarium fish industry tolerated for years fish being collected using cyanide. This not only destroys the reefs where the fish lives, but the fish thus caught, which were being imported into the USA, and invariably died on first feeding.

I would presume that importers could avoid such horrors quite straightforwardly, but they weren’t at the time. I don’t know the present status of these activities, in the Philippines and elsewhere. I hope they are being suppressed, and that the aquarium industry distances itself from such activities.

BZA: Science Magazine called you “arguably the world's most prolific and widely cited living fisheries scientist,” yet they also referred to you as an “outsider.” What do you think they meant by that, and do you consider yourself an outsider?

DP: I have been a long time an outsider in my discipline of fisheries biology because it has long been driven by colleagues working in Europe and North America, usually working for governments, and managing local fisheries. I, however, was working in the tropics, and tropical developing countries usually don’t manage their fisheries. Since 1994, I have been in North America, but I'm working on issues related to marine conservation. This again may make me some sort of an outsider. However, I believe that conservation biology and fisheries science are gradually going to merge, so maybe I won’t be an outsider any more.

BZA: Outsider or not, your impact is undeniable? Ray Hilborn (University of Washington, Seattle) said that you have had “a greater impact on the field than any member of [your] generation.” About what impact are you most proud?

DP: Being an outsider generally means that one's voice is not heard. For my part, I can’t complain: people hear me. However, fisheries and conservation biologists are not heard by the people who matter: politicians and high-ranking civil servants; thus, we continue to see decisions being taken which literally destroy fisheries—like, for example, the recent granting of higher fuel subsidies to French fishers.

The impact I have on my colleagues, and on the younger generation, is mainly indirect, e.g., when they use online databases such as FishBase, modeling tools such as Ecopath, or concepts such as “shifting baselines” or “fishing down the marine food web,” which I have been involved in developing.

The word ‘proud’ does not capture the feeling this leads to—besides, pride goeth before a fall. Rather, I would say I'm deeply satisfied that these tools have been found useful.

BZA: You have spent a lot of your career working in the developing world, where you have made major contributions to gathering scientifically valid data in data-poor tropical nations. Have you seen a change in the way that fisheries are managed in developing nations based on scientific data?

DP: The reason why I turned towards conservation in the mid 1990s is because I was not seeing the work of fisheries scientists—local and foreign—working in tropical developing countries being put to use. In fact there was a complete disconnect between political decision affecting fisheries and the work of fisheries scientists, even within the same ministry. This is the reason why I now work with environmental groups, which can carry one’s message to a broader public and exert pressure. This, incidentally, is true also for developed countries in which I have found, much to my initial surprise, that this disconnect is also common.

BZA: Your paper “Towards sustainability in world fisheries” begins with the statement that “Fisheries have rarely been ‘sustainable’.” I assume you are talking mostly about fisheries for food here, but what about the aquarium industry? Is the aquarium industry, in your opinion, sustainable or not?

DP: The statement that fisheries have rarely been sustainable is based on the fact that for sustainability to occur, the exploitation of a stock must result in a similar yield for decades, subject to variations of the environment. On the other hand, fisheries are not sustainable when their operations deplete local stocks, and the fisheries can be maintained only by shifting from inshore to offshore stocks, and then to deep-sea stocks, etc.

The criterion for an aquarium fishery to be sustainable is thus, simply, can maintain its catch without expanding its range. This criterion is not arbitrary: it is the essence of sustainability that things should remain similar from year to year. If a fishery can survive only by expanding its reach, then it is not sustainable.

BZA: Later in the same paper, you claim that “[z]oning the oceans into unfished marine reserves and areas with limited levels of fishing effort would allow sustainable fisheries...” Have you followed the recent legislation regarding Hawaii and the regulation of fish collectors for the marine ornamental industry? Part of the original legislation, introduced in January 2008, proposed a complete ban on some herbivorous fishes such as the yellow tang (an aquarium staple). What is the role of herbivorous fishes on the world’s tropical reefs, and how should aquarists approach species such as the yellow tang based on the ecological niche they fill?

DP: I don’t know specifically about the yellow tang and about the situation in Hawaii, but I know about the role that herbivorous fish play on coral reefs. Essentially, what they do is consume the fleshy and filamentous algae, which, left ungrazed, would smother the coral reefs. Lots of coral reefs, throughout the world, suffer, and are eventually killed by algae because parrotfish and other herbivores have been removed by fishing.

I do not see why, with the scientific advances available nowadays, we cannot have a closed system for the production of herbivorous coral fish for aquaria, and why the aquarium industry should depend on supply from the wild. This is probably a problem that can be solved with a few PhD scholarships to the University of Hawaii, or another place where you can tap into the energy and the brains of graduate students.

BZA: I know you received the Murray Newman Award for Excellence in Marine Conservation Research from the Vancouver Aquarium. As you might imagine, many public aquaria provide inspiration for marine aquarium hobbyists. In your opinion, what role have public aquaria traditionally played in regards to conservation? What role should the aquaria of the future play?

DP: I mentioned earlier that aquaria have been crucial for me for my first scientific insights. I believe that aquaria also play a key role in making the wonders of the aquatic world accessible to people who can’t dive. Aquaria like those in Vancouver or in Monterey are magic places, and in fact, the latter aquarium has been a major element in the life of my two children, whom I dragged through the exhibits even when they might have preferred to go to the movies.

BZA: You were once quoted as saying that “[m]ost people do not perceive fish as wildlife.” Will you explain what you mean by that and why it is a problem?

Wildlife in North America is composed of raccoons, wolves and bears—animals with personalities, who have faces, and emotions we understand. Fish remain impassible when we hook them, and don’t scream when we eviscerate them. They are perceived as things, at best like flowers, often like cabbages. Cabbages are not wildlife. This is a reason why fish conservation has such a hard time.

BZA: Following up on the last question, you have suggested that people need to engage with fisheries in a manner that goes beyond a consumer-product relationship. “I don’t like the notion of us being reduced or engaged mainly as consumers rather than as a citizen,” you have said regarding our consumption of seafood. Does the same hold true for aquarists? What can aquarists do to be citizens instead of simply consumers in regard to the marine aquarium hobby?

DP: Aquarists are not consumers of fish; I suppose they are admirers of fish. This is the reason why it is important for aquarist organizations to educate their membership on how to reduce negative ecosystem impact. Then, the aquarium industry would not generate a demand for fish that are caught unsustainably, or for live rocks which ought never to be harvested from live reefs in the first place. I can easily see this informed industry being an ally to coral reef conservation organizations throughout the world. I don’t know that it is right now. This would be a worthwhile project.

BZA: Indeed that is a worthwhile project. We hope increased dialog between conservation-minded scientists like you and hobbyists like those reading Blue Zoo News will help to further that project in a meaningful way. Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with us, Dr. Pauly. We would welcome your input at any point.

To learn more about Dr. Pauly and his work, you can visit his website at www.fisheries.ubc.ca/members/dpauly/. The papers mentioned in the interview can be downloaded from Dr. Pauly’s web site. Also, you may be interested in visiting www.seaaroundus.org. Sea Around Us is a site that investigates the impact of fisheries on the world's marine ecosystems. It is a partnership between the Fisheries Centre and the Pew Charitable Trusts and is led by Dr. Pauly.

Published 3 June 2008. © Blue Zoo Aquatics

|